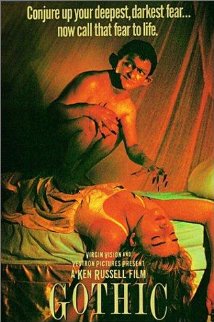

This is a promotional poster for the film. It was found on the Internet Movie Database at http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0091142/

Gothic reenacts the summer of 1816, when Mary Godwin Shelley first conceived the idea of Frankenstein in Lord Byron’s summer home in Italy. The film, under the direction of Ken Russell, premiered in 1986 and takes a psychedelic approach to the events of that summer, and of one night in particular. Gabriel Byrne plays Lord Byron, Julian Sands plays Percy Shelley, Natasha Richardson plays Mary, and Myriam Cyr plays Claire Clairmont, Mary’s half-sister. Dr. Polidori is played by Timothy Spall. The screenplay was written by Stephen Volk, and although the film is not on Netflix or HBO, it can be found in its entirety on YouTube. [1]

Synopsis[]

Gothic begins with tourists observing Lord Byron’s Villa Diodati from across the river as Mary Godwin, her soon-to-be husband Percy Shelley, and half-sister Clair Clairmont arrive for the summer. The friends meet Lord Byron inside and are introduced to Dr. Polidori, Byron’s personal physician. Sexual tension between all parties, both hetero- and homosexual, are evident, and it’s clear that Claire and Byron are lovers. The guests are shown to their rooms and reconvene for dinner that night. During dinner, conversations about death, decay, and the devil abound amidst drugs and alcohol. Next, a game of hide-and-seek ensues that results in Shelley standing atop the roof naked during a terrible thunderstorm. He finally climbs down, very excited about the seeming life-giving effects of lightning. The group gathers around the fire, reading ghost stories out of an old book; the telling of the ghost story is laced with drug-induced hallucinations and sexual fantasies, and leads to the group deciding to make up their own horror stories as a competition. Byron asks them to conjure up their deepest fears and call them to life as inspiration. The group gathers around a skull and performs cult-like chants; Claire makes the first attempt to follow Byron’s instructions and her encounter with the supernatural force present resembles a sexual climax until she falls to the ground in convulsions. They take her to her room while the storm continues on, and it is clear that another being is in the house with them. All parties continue taking drugs and each has their own confrontation with this “other presence”, but the chilling encounters seem to be all in their heads. Competition for Shelley’s affections between Mary and Claire intensifies as the film progresses, and there are several intense sex scenes between the parties, namely Claire and Byron. When the group finds that the monster they conjured from the dead has possessed Claire, they realize that they must send the monster back the way it came via the skull. Mary does not want to participate, however, and smashes the skull with a rock just as the devilish chants are intensifying. She aims to kill Lord Byron as well, but Shelley jumps to save him and the two men engage in a long kiss. Mary runs away and finds herself in a room with multiple doors that each depict a different death in her life. Shelley saves her from suicide and the next morning, all is well. The friends eat breakfast together and discuss Mary’s ghost story, which we know turns out to be Frankenstein. The film ends in present day with a group of tourists gazing at the villa while a tour guide tells of each person’s life after that fateful evening.

Major Themes[]

Sexuality[]

Gothic clearly supports the idea of sexual freedom, and the characters use the slogan “free love” frequently to explain their promiscuous actions with one another. This is most likely a result and remnant of the sexual revolution of the 1960s and 1970s, but speaks to larger social issues such as feminism and homosexuality. Claire Clairmont and Mary represent feminism, and homosexuality is represented primarily by Dr. Polidori. Sexual ambiguity is also a factor and is embodied by Percy Shelley and Lord Byron’s relationship. The original Frankenstein has been critiqued as a prototype of feminism, though it is subtle. The women in Mary Shelley’s novel are passive and nearly nonexistent, but the absence of them seems to indicate that they are actually the cure to every ail. In Gothic, Claire and Mary play different and similar roles to the women in the novel. Claire is much different than the women in Shelley’s novel in the way that she is portrayed as ultra sexual, vocal, active, and unrestricted. On the other hand, Mary fulfills Shelley’s implications about women by smashing the skull and ultimately ending the curse of their monster. Homosexuality is addressed by Polidori’s character, who is infatuated with Lord Byron. Polidori is tormented by the others for liking men, and he repeatedly tries to kill himself because of their teasing. This could speak to the social burden of being homosexual, both then and now. Sexual ambiguity is evident in Byron’s relationship with Percy Shelley; the two men are often very close physically and even engage in a lengthy kiss toward the end of the film. Mary is deeply upset by the men’s actions with one another, and even goes so far as to call Lord Byron the devil himself. In this way, it is hard to determine if the film’s director and screenwriter support or condemn homosexuality. It is impossible to watch Gothic without noting the immense amount of unrestricted sex, though it is unclear if the concept of “free love” is actually good or bad for those involved.

Creation as Monstrous and Deadly[]

Monstrous creation is a theme that is also present in Mary Shelley’s original Frankenstein, and there are many scenes in Gothic that nod to this theme in the famous novel. Victor Frankenstein breathes life into a patched-together dead body and is forever haunted by it. The monster is an agent of death in Victor’s life and represents ultimate havoc. His deep desire to escape his monster echoes Mary’s cry to “get out” of Byron’s mansion in the film because nowhere is safe. Although the group never creates a physical monster, it is clear that a malevolent presence is in the house with them. The “monster” in Gothic is the source of all chaos; it is a combination of everyone’s darkest fears come to life. This theme is addressed in a conversation between Byron, Percy, and Mary. Percy says, “We dreamt of creation and the defiance of God!” and Mary replies, “And our punishment is that we have created.” When it becomes clear that the monster cannot be destroyed the way it was created, Mary says, “We’re dead. It’s shown me the torture it has in store for us, our creature. It will be there waiting in the shadows in the shape of our fears, until it has seen us to our deaths.” These quotes echo the theme of creation as a monstrosity that is present in the original novel, as well as almost every other adaptation of Frankenstein. The monster in Gothic, though it is not a physical being, is a culmination of the worst parts of everyone’s mind, and this is how the creature lives on, forever haunting Mary, Percy, Byron, Claire, and Polidori. [2]

Reception[]

Most likely due to its psychedelia and crazed depictions of characters, the film gained mixed reviews from critics. However, actors in the movie defended Russell’s portrayal of these literary giants. In one interview with the New York Times, actor Julian Sands said, “I think these portraits are rooted in reality…These were not simply beautiful Romantic poets. They were subversive, anarchic hedonists pursuing a particular line of amorality.” [3]The film won two 1987 International Fantasy Film Awards, one for Best Actor (Gabriel Byrne), and another for Best Special Effects. Gothic was nominated for Best Film in the International Fantasy Film Awards, but did not win. [4]

Significance[]

The conception of Frankenstein is equally as important as the novel itself. Recreating the night that Mary Shelley first brought her idea to life gives a better sense of the themes that are present in the original novel. Gothic is not the only Frankenstein heritage film - Rowing with the Wind also focuses on the summer of 1816 and can be found on Netflix. However, the two films sport significant differences. Gothic is much more horrific, and plays into the idea of the mind as monstrous more than Rowing with the Wind does. In addition, drugs and sex have a presence in Gothic that they do not have in Rowing with the Wind. The timeline of the two films is also dissimilar; Rowing with the Wind follows the lives of the characters several years after that fateful summer, while Gothic truly focuses on one night throughout the entirety of the film. Perhaps the largest difference between the two films deals with the monster itself. In Gothic, the monster is only a product of the characters' minds, and torments them by exploiting their deepest fears. In Rowing with the Wind, however, the monster is very real and actually has agency.

This adaptation of the Frankenstein narrative is unique because it engages both the novel as well as the biographical information regarding Mary Shelley that influenced the creation of the creation of the story. Mary Shelley lost her first child and always wished that child could come back to life somehow. This idea of death turning into life was the primary force behind her famous novel. Viewers of Gothic receive this pertinent information, allowing them to understand Mary Shelley in a way that most other adaptations cannot. The film is culturally relevant as well because it depicts drug use and casual sex, which had started to become more prevalent in society just a few years prior to the film’s release.

References[]

Darnton, Nina. "At the Movies: Gothic." The New York Times 10 Apr. 1987: C16. Web. 6 Apr. 2015.

“Gothic.” Internet Movie Database. Amazon, 1990. Web. 6 Apr. 2015.

Russell, Ken, dir. Gothic. Perf. Gabriel Byrne, Julian Sands, Natasha Richardson, Myriam Cyr, and Timothy Spall. Pestron Pictures, 1986. Film.

Also, check out the full Mary Shelley Wikia page, complete with analyses of her original novel and the numerous adaptations here [5].

Contributor: Rachel Haynes